“The Burning Trough” is one of the weirdest fairy tales ever.

Franz Xaver von Schönwerth’s collection, The Turnip Princess and Other Newly Discovered Fairy Tales, features many stories that seem familiar in general outline: the old pieces in a new order. And then there are a few that are… hoo boy.

Briefly, “The Burning Trough” goes like this. A farmer has three daughters who are mostly concerned with their own dowries, so they spend all day spinning instead of helping him on the farm.

Okay, no. Wait. I already have questions. Since when is “spinning all day long,” or any work, considered selfish in a fairy tale? Laziness is always a problem punishable by all manner of tortures, but this? It’s because they “never took a moment to help out their father.” I get it that their work is for their own benefit rather than directly for the collective’s, but securing good marriages isn’t exactly sitting on their buns eating hors d’oeuvres, either.

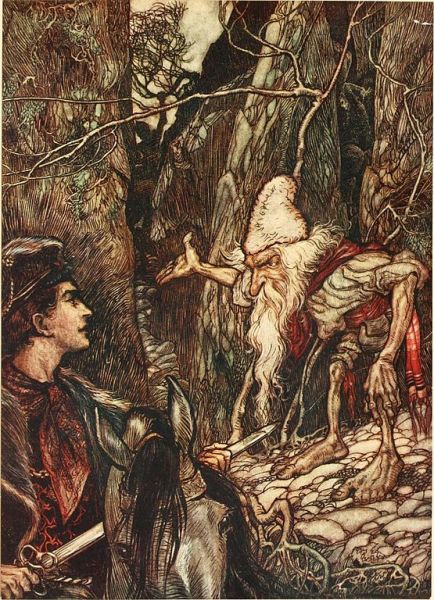

Daddy Farmer goes into the woods, trips on a stump, a dwarf jumps out and says he’ll make the man’s fortune forever if he’ll let him sleep with one of his daughters. Farmer okays the deal. When he gets home, the table is set with beautiful dishes, so everyone knows the dwarf can follow through. Eldest daughter says she’ll take one for the team. She’s a sport.

I’m puzzled by how very little hesitation Father seems to have about this arrangement. Don’t fairy tale fathers usually express some kind of regret or have to be coerced? Perhaps if all the girls care about is their dowry, it’s fair to whore them out to a dwarf as a retirement fund.

But get this: “When night fell, there was a knock at the door, and the eldest opened it. All she could see was a trough in flames; terrified, she slammed the door.”

What the actual… What was THAT?

A trough? Like, a container for animal food? I’ve read a lot of fairy tales and folk tales, but other than Jesus’ manger, I cannot recall another significant or symbolic trough. The only clue I can get from it is its shape, but that just confuses the issue further. In general, anything shaped around an empty space (a chalice, a cup, etc.) is suggestive of the female. But the dwarf is male. He changes during the story, but he’s always male. Unless it’s not the dwarf. But the dwarf says he’s coming, she opens the door, there’s the trough… It’s hard not to equate the two. There’s no reason not to. Except that the whole thing is a complete acid trip.

The fire is slightly less problematic. He’s there to initiate sex, after all. He’s got an impressive supply of mana to work with, including (presumably) enough magical power to make the family rich. Apparently he’s too hot for her to handle in more ways than one. So far she’s been concerned only with her own advancement rather than, for instance, filial love, and she’s agreed to lie with a dwarf for material gain, so it makes sense that actual passion would be foreign and scary.

Note: I do not mean to imply that a dwarf is not worth lying with for his own sake. You’re familiar with Tyrion Lannister? I rest my case.

But… a trough. Why? Why. Think think think.

Anyhow, rinse and repeat for Daughter #2. By the time the dwarf makes his way down to the youngest, he’s insulted and angry. But luckily for him and for her, Anna (who hasn’t been distinguished from the other two until now) is up to… doing… whatever this is. “When she saw the trough in flames, she jumped into it, hugged and kissed whatever was there, and asked it to come to her room. At that very moment, the monstrous thing” turns into a handsome prince. They get acquainted (ahem) and in the morning he gives her three gold sewing implements: “a spindle, a bobbin, and a spinning wheel.” He says he’ll DM her later (I’m paraphrasing here) and promptly ghosts her.

“Whatever was there”? “The monstrous thing”? What could we be talking about? It’s not even the dwarf. The dwarf is at least referred to as “he”; this is a thing, a whatever. In a trough. Which is on fire.

In general, it’s a “Frog Prince” setup: once the princess steps up to the plate and makes the frog welcome (ahem), the spell is broken. And maybe spending quality time with a talking amphibian is no worse than leaping into a flaming manger and making out with whatever you find.

But I’m still scratching my head over the trough. Is it a trough just so that she can signify her unquestioning enthusiasm by jumping into it? Is that all? Maybe in another setting it just as easily could have been a bathtub or a Prius or some stylish carry-on luggage. On fire.

Even so, a person inside a cave/cup/sphere/suitcase is usually connected to the idea of pregnancy or birth or transformation. Anna gets INTO the trough in order to transform the dwarf and “birth” the prince…? Is she a sort of mother? If so, why does her little man (hmm…) bring his own uterus to the party?

I’m interested in the prince’s choice of gifts, too. The story starts by tsking over the daughters’ spinning habit, but apparently their whole SoulCycle cult is more than fine with the actual fiance, who seems to endorse their activity of choice by giving Anna the shiny pretty accouterments.

When the prince doesn’t come back, “lovesick” Anna takes her gold toys and goes to find him, getting help first from the moon and then from the sun.

This bit seems familiar: when the beautiful is unmasked, it disappears. “Cupid and Psyche” comes to mind, but there are others.

“And that was when the mountain exploded and tossed her down into a cave.”

I know there’s no point asking logical “why?” questions at a fever dream of narrative like this one. But symbolically… Maybe getting the help of the Moon and (especially) the Sun inflates her (in the Jungian sense, not the bicycle-tire sense) and the getting “tossed down” is a form of catastrophic metanoia. Entities like the Sun and Moon often won’t even cooperate with a hero who isn’t ready. Then again: Phaethon. Good point. Enough said.

The next paragraph is so confusing that I fear a translation issue, or just pronoun problems. Or just LSD.

“There she found an old woman who was waiting on her beloved. Anna asked if she could sleep next to the man who was her master. Every night she gave the woman one of her golden gifts.”

First, I’d like to be sure that “waiting on” is truly the intended phrase. Is the old woman a servant of the beloved, waiting on him? Or is she waiting for him? It must be the former, because there’s no point in Anna’s asking to sleep next to “the man who was her master” if said master isn’t even home.

But whose beloved is it? At first I assumed it was the old woman’s, but it makes more sense for it to be Anna’s prince. Is this a process of taking said beloved away from the old woman? That would explain the payments in gold, just as the farmer was promised enough wealth that he “will never have to work again” (once Anna gets into the trough to fulfill the bargain, the father and sisters are presumably irrelevant, as they are not mentioned again). But the old woman is a servant, not his lover or his mother. “Waiting on” does not imply any authority over the beloved at all, yet Anna needs to pay her off.

Some of this part in the mountain seems to mirror the beginning of the story. Instead of the dwarf’s getting permission from the old farmer to sleep with Anna, Anna gets permission from the old woman to sleep with… the dwarf? The prince? Some third incarnation? I still can’t quite tell who this “beloved” is. First Anna jumps into the trough to prove her devotion; then she tumbles into a cave. Sleeping next to… whatever it is?… breaks a spell in both cases. It takes the dwarf all three sisters before he finally gets some action; Anna gives up all three of her “golden gifts.”

I’m befuddled by the blank space where the dwarf/prince should be in both instances. In the first, he is “whatever was in there… the monstrous thing.” In the second, “the man who was [the old woman’s] master” is presumably there, but if he’s the prince–or the dwarf–we hear nothing about that. The entire procedure is a bargain between the old woman and Anna. Essentially, Anna uses the gold and her presence in the master’s bed to buy the prince out of his enchantment. But if the dwarf was pushy and angry, the prince here is so passive as to seem absent. I mean, if Anna got into bed with me, I think I’d notice.

I know you’re wondering, so I won’t leave you in suspense.

“On the third morning the spell was broken. The mountain and the cavern had disappeared. In their place was a magnificent castle belonging to the handsome prince. Gratitude and love united the two in marital bliss.”

Of course this isn’t the first time the monster turns into a prince: start with “Beauty and the Beast” and go from there. To embrace one’s darkness is to free it and bring it into the light. And it’s interesting that the gifts she earns when she first sees the prince are the very same gold pieces she uses to ransom him. Part of her reward for jumping in at the beginning is the means to keep (or get back) what she finds.

German speakers: Is there something I should know about the word for “trough”? Do tell. Because otherwise, that is just wacky.